American cinema

Lion (Garth Davis, Australia/USA/UK, 2016)

American cinema, Australian Cinema, Blogpost, British cinema, Film reviews, Transnational Cinema, UncategorizedThere is a sequence in Lion where Saroo (Dev Patel) and his soon-to-be girlfriend Lucy (Rooney Mara) walk to a party on opposite sides of the street.

Lucy does a wee dance, and Saroo then copies her – the pair thus doing some cute romance as they swap dance moves from across the road that separates them.

The moment is an uncredited homage to Spike Jonze’s short film, How They Get There (USA, 1997), which you can see in full below (for as long as it remains on YouTube).

Given that Lion is a film about a young boy who by accident becomes separated from his family and who ends up being adopted by Australians, and given that the film is based upon a true story, it seems strange to have this extended reference to Jonze’s film included.

For, while Jonze’s is a playful and witty short, Lion seems to be in the business of taking itself very seriously – as perhaps it should do given that it is a film about a topic as weighty as transnational identity, and which is seeking to pick up various awards during this year’s season. The homage, therefore, shifts the film tonally from serious to playful in a way that jars with the what the film otherwise seems to set out to achieve.

So let us say that Saroo and Lucy had seen How They Get There (these characters do supposedly live in the real world, after all, meaning that they may well have done). Surely the inclusion in the film is therefore justified – a kind of audiovisual exchange that could just as easily be the characters bonding via conversation over, say, their love of Aravind Adiga or Powderfinger (also real world figures)?

Well, maybe. But since Lion so clearly adopts this scene from Jonze, it simply feels tired, unimaginative and unoriginal – as if the filmmakers could not themselves come up with anything better than nicking someone else’s idea in order to convey romance. One’s confidence in the rest of the film is undermined: how much more of this film is entirely derivative?

More than this. There is a cinema in the world where such shifts in tone are in fact commonplace, such that they become perhaps even the defining feature of that cinema.

I am of course talking in quite a general sense about Indian cinema, with the Mumbai-based industry known as Bollywood generally functioning as its metonymic figurehead.

Lion is a transnational co-production, as the stated involvement of Australian, American and British monies makes clear above. And yet the film is also largely set in India, with locations including Kolkata and Khandwa, which lies close to Saroo’s home town of Ganesh Talai. What is more, the film also features numerous performances by Indian actors. So, one asks oneself, where is the Indian economic involvement in the film?

Or does the tonal shift marked by the adoption of Jonze’s idea also mark the adoption of ideas (tonal shifts themselves) from Indian cinema, which in turn marks the adoption of Indian cinematic resources for this film – which is a film about the adoption of Indian boys by white Australians?

There are plenty more things to say about Lion, but I would like to limit myself to three things – the first of which relates to How They Get There.

For, in Jonze’s film, things end badly as the male dancer gets run over, with the driver of the car perhaps also dying – and the male dancer’s shoe ending up in a gutter by the side of the road.

Does the reference to this film in Lion, therefore, signal a similar pessimism with regard to Saroo? While the film clearly is about ‘How They Get There,’ are we to believe that Saroo is, as it were, a shoe in a gutter – looking up at the stars that might help him in the developed world? There seems to be no clear analogy, but any way that one looks at it is never far from offensive.

Indeed – to move on to my second point – there is another strange sequence in the film where Saroo’s adoptive mother, Sue (Nicole Kidman), explains that when she was 12 she had a vision whereby she saw herself with a ‘brown boy’ – and that this is what drove her not to want to have birth children, but to want to adopt kids herself.

The daughter of an alcoholic, Sue in some senses seems to declare here that Saroo is partially an object that helps her to get over her own traumatic childhood. Which I guess is fair enough, except that this again reduces Saroo to simply a brown boy who may not want to be, but who is indeed the plaything of sorts of white Australians. No wonder that Saroo’s adopted brother, Mantosh (Divian Ladwa), is himself so troubled.

In this way, it seems oddly fitting that Saroo is not, in fact, Saroo’s real name. His infantile tongue could not properly pronounce his name (nor the name of his home town), and so Saroo is the result of the boy (played by Sunny Pawar) trying to say Sheru (meaning lion), and Ganestalay his attempt to say Ganesh Talai – a town that no one could find as a result of this difference.

What a thin thread possibly prevented Saroo from being able to find his way home. Nonetheless, the erasure of his Hindi roots through this ‘error’ does, as mentioned, seem oddly apt through its occultation of Saroo’s origins.

Of course, Saroo is haunted by his past and he does finally discover his origins – so at least we see that he cares for truth and is haunted by his privilege knowing that his mother is a labourer who carries rocks for a living while he enjoys boats and aeroplanes (and visions of his past from a drone – with his discovery of his past enabled in large part by the surveillance technology of Google Earth).

In other words, Lion clearly is a film about worlds separated by technology and in particular transport as a means of defining humans according to their different abilities to travel/move (even if true, it is oddly apt, then, that Saroo’s destiny is changed by his inadvertently being on the wrong train – the great distance that it covers from Khandwa to Kolkata signalling his destiny to be catapulted into a new, more mobile world).

And we are glad that Saroo is saved from this world, even if we see him running and laughing and loving his family in Ganesh Talai. For it is also a world defined by manual labour, paedophilia, child abuse and uncaring authorities. Saroo really is better off, it would seem, in Australia – and his rescue is thus in some senses justified, even if his adoptive mother has dimensions of the would-be White Saviour.

Dev Patel gives an excellent performance as Saroo. The film as a whole is powerful. But as the film ultimately endorses the fast pace of modernity at the expense of the slow pace of those pedestrian labourers who function as the very props upon which this modernity is based (it is the labour of his birth mother that brought Sheru into the world, even if Sue takes credit for raising Saroo), so, too, is the film constructed according to the fast pace of western films.

That is, the film has rapid scenes, often cutting into action and getting the viewer to infer what has happened – rather than allowing the viewer to see events unfold for themselves.

In this sense, we regularly see Saroo/Patel at points of high emotion – but the film in this regard does not show us ‘how they get there.’ That is, we do not see the onset of emotion, the change that takes place – we just see the emotion itself, with the emotion itself thus becoming symbolic, a symbol of emotion, rather than an emotion grounded in the real world of change and becoming.

The film’s decision to rush emotions in this way – to be too busy/in the business of business to want to take us through the complexity of emotion – reflects the privileged speed of the highly technologised First World, where emotions become empty because of their own speed, rather than real because slow and enworlded.

In its form, then, the film undermines what it otherwise would seemingly want to achieve: we want to connect with people across boundaries, but really what we are seeing are power games and the use of other people and their real lives for the purposes of our own entertainment, edification and comfort. This makes for troubling viewing, even if I also was swept up personally in the story that I was seeing.

While Patel seems excellent as Saroo, then, it also seems a shame that he is edited in such a way that we do not really get to see him act. Or rather, his performance is reduced to acting as a result of the editing: here is Saroo unhappy, here is Saroo sad, and so on. To get beyond acting exposed as acting, to get to acting as an embodied performance, we need to see the transitions; we need to see how they get there.

Oddly, such a transition is shown in the film – but by Sheru’s mother, Kamla, when they are reunited. I believe that this moment is performed by Priyanka Bose (she plays Saroo’s mother when he is young; it is unclear whether it is still her but aged via make-up when they finally meet again).

In a few brief moments of screen time, we see Bose carry out an extraordinary performance of recognition and then emotion as she recognises her boy. And yet what plaudits for Bose in the celebration of the film at awards season?

Furthermore, in a few brief instants we here sense a story that we never otherwise got to see – the story of an illiterate labourer whose son has been taken from her in rural India. How much more interesting might that film have been, rather than the troubles that a boy had in discovering his hometown through the use of Google Earth?

That we see a film that privileges the privileged masculine perspective is perhaps profoundly western. If, we wanted to watch a film featuring the female perspective, then we likely have to discover a different cinema – perhaps even the cinema of a place like India, where a masterpiece like Mother India (Mehboob Khan, India, 1957) dares to tell precisely the story of a female labourer struggling to bring up her children in the Indian countryside.

(Much as I tend to enjoy the performances of Casey Affleck, the performance from Bose in Lion reminds me of how Michelle Williams acts Affleck off the screen in Manchester by the Sea, Kenneth Lonergan, USA, 2016, even though she has minimal screen time and even though her big scene is scripted basically to suggest that she still is in love with the man who is largely responsible for the death of her children – i.e. it is a male fantasy-fulfilment.)

(This in turn reminds me that both Lion and Manchester by the Sea continue the trend of films about dead, lost, and otherwise problematised babies and children – as I have written about elsewhere. It is the preoccupying theme of contemporary western cinema.)

Forasmuch as it is well made and enjoyable, then, Lion seems to have adopted various things from various other places not in order to present us with any changed vision of the world, but to replicate the vision of a superior western, technologised, cinematic world – even if this world is built upon the labour of people like Kamla, whose plight remains invisible.

How we got here – to such a world that seemingly is made up of different worlds – is hidden.

And yet it might be the most important (hi)story for us all to learn.

Philosophical Screens: Goodfellas (Martin Scorsese, USA, 1990)

American cinema, Blogpost, Film education, Philosophical Screens, UncategorizedThis post is a written version of the thoughts that I shall be giving/gave about Goodfellas on Monday 23 January 2017 as part of the London Graduate School‘s Philosophical Screens series, and part of the ongoing Martin Scorsese retrospective being run by the British Film Institute.

Goodfellas tells the story of Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), who has always dreamt of being a gangster. As he rises up through the ranks of New York’s Italian mafia, however, his life begins to unravel in two ways. Firstly, as a half-Irish/half-Italian, he is not 100 per cent Italian and so cannot Get Made to a full fledged mafia boss. Secondly, against the advice of his boss, Paulie (Paul Sorvino), Henry goes into the drug business.

When Henry’s operations thus come unstuck with the law, it would appear that he cannot turn to his mafia family in order to rescue him; more likely is that they will kill him. And so he breaks both golden rules of being in the mafia, and he rats on and betrays people that might otherwise be his friends.

Henry’s situation is not helped by the fact that he is in cahoots with Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro) and Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci), both of whom are loose canons, with the latter being particularly psychotic – taking pleasure in murdering various minor hoods with whom he happens to cross paths, and one major hood, Billy Batts (Frank Vincent), whose murder will eventually bring about Tommy’s own undoing also.

The film is famous for various lines, scenes and sequences, including when Henry takes his wife-to-be, Karen (Lorraine Bracco) on a date to the Copacabana club, entering via the delivery basement entrance and touring her around the kitchen before entering the club where a table and drinks are laid on as the owners and other clients seek to impress the unassumingly powerful Henry with gifts and gimmes.

Other examples include Tommy grilling Henry about how he is funny (‘Funny like I’m a clown? I amuse you?’), and a confrontation between Henry and Jimmy in a diner involving a celebrated dolly zoom (whereby the camera tracks backwards and zooms in at the same time, thus giving a vertigo effect) as Henry realises that Jimmy is setting him up for death.

However, a detail in the film upon which I’d like to focus and which will form the starting point of my analysis of the film is Morrie’s wig.

Morrie (Chuck Low) is a small-time hood who runs a wig shop. When we first meet him, we see a television advert of Morrie explaining how good his wigs are as he jumps into a swimming pool and as he is surrounded by women who kiss him on the cheek.

The advert is deliberately cheesy, and after seeing it, the camera pulls back to reveal that we have been watching the image of Morrie on a television screen that loops his advert. The camera turns to Jimmy, who watches the advert, and then back through Morrie’s shop to Henry, who talks to Morrie in person out back.

Morrie is refusing to pay Jimmy the interest on some money that he owes – which leads Jimmy to start to strangle Morrie with rope as Henry receives a phone call from Karen. As Jimmy strangles Morrie, his wig comes off – demonstrating that he is a small-time hood who clearly lies, since his advert declares that his wigs can withstand hurricanes (or words to that effect).

The moment is – like much of Goodfellas – amusing, even if violent. (Jimmy lets Morrie go – on this occasion.)

The aim here is not to discuss the comedy of Goodfellas, and perhaps of Scorsese’s work more generally, not least because this is something that John Ó Maoilearca will discuss/did discuss in greater detail at the Philosophical Screens event. That said, I shall end by making reference to the comedy of his work.

Rather, Morrie’s wig allows us to think about the ethos of Goodfellas as being one based upon excess. For, not only is a wig that is obviously a wig funny (especially when it falls off), but it also demonstrates the way in which humans use things that exceed their natural abilities/possessions in order to demonstrate (in Morrie’s case) a kind of youth, strength, virility – and thus power.

In this particular instance, Morrie’s pretensions to power are ironic given that he is about the most camp character in Goodfellas (although he is married) and also deeply insecure (hence his constant talking whenever he is onscreen).

The fact that we see Morrie’s wig at first on a television screen also plays into this. Jimmy himself says that Morrie should not have wasted money on the advert given that he could have used the money to pay him back. That is, the advert is excessive. Furthermore, the advert itself functions as a kind of ‘bad wig’ – in the sense that it is intended to show mastery of the image, but in fact comes across as cheap.

With both the wig and the advert, then, we get a sense of Morrie aspiring to power, but not being able to attain it – in part because the workmanship of both is too poor. Morrie aspires to excess – just as his fellow hoods do – but in some respects he is not excessive enough to be a successful gangster.

However, while Morrie might be a figure of fun (who ultimately gets killed by Tommy for being a probable liability after the crew steals US$6 million from a Lufthansa flight), Morrie in some senses unlocks the whole of Scorsese’s film and the philosophy of excess that it sees as key to the (attractions of) gangster life – even if at times this excess is disavowed.

For, while the film equally shows Jimmy criticising Johnny Roastbeef (Johnny Williams) and Frankie Carbone (Frank Sivero) for spending the Lufthansa money on pink cadillacs and mink coats – i.e. for being excessive – it is precisely this excess that Henry desires and which Karen, too, also finds seductive. Indeed, just after Jimmy has bust Frankie and Johnny’s balls for their profligate spending, we see Henry arrive home at Christmas saying that he bought the most expensive tree they had: Henry likes extravagance.

As we see the Hill family Christmas, Scorsese’s camera tracks in towards a bauble that hangs from Henry’s all-white Christmas tree. Why is this shot here? What does the bauble signify? The fact of the matter is that it is hard to tell. But the bauble is shiny and comes to fill the screen. That is, the shot itself is ‘excessive’ in the sense that it is unnecessary. In this way, Scorsese with his film does not simply show us excess, but he also takes us via his camera movements into the mindset of finding excess attractive. His film itself is excessive, full of ‘unnecessary’ shots and moments, which themselves come to be a chief pleasure of the film beyond simply the telling of a story.

(What is a bauble if not an excessive feature that is part of the festival of excess that Christmas under consumerism has become? These fragile balls that hang from trees for no reason, and yet which we pack away carefully each year, scared that they might break, too thin to hold in hand for fear of crushing them… The bauble perhaps is total excess.*)

With excess in mind, the Copacabana shot comes into its own. As Henry leads Karen around the kitchen, we can – if we pay close attention – see that Henry basically does a lap of the kitchen by ignoring the fact that he can go straight through into the restaurant. The lap of the kitchen is pure excess: he is showing off to Karen.

But more than this. In having a single, unbroken tracking shot that also takes us around the kitchen and into the restaurant, Scorsese is also showboating, showing off to us, showing us a film that also is excessive, and which certainly exceeds the perceived necessity of ‘economic storytelling’ considered to be so dear to the American film industry (the ethos of getting rid of everything superfluous, not least because time is money and it costs a lot of money to put it in there; Scorsese’s film, like the gangsters themselves, dishes out in spades ‘fuck you money’ in terms of superfluous shots).

What emerges from this showboating/showing off, though, is that Scorsese does not show us something that exceeds cinema. Rather, through the excess of Goodfellas, we come to realise that cinema is perhaps excess itself – especially when it lampoons the smaller television screen for aspiring to excess but failing miserably à la Morrie’s wig.

In other words, what Henry aspires to be or to become is cinematic, to lead a life of excess. And this becomes clear as we see how Scorsese’s film is rammed full of never-ending camera movements, which are punctuated not so much by static images as more specifically freeze frames, of which there are numerous throughout the film. In other words, even when Scorsese stops his frenetic camera, it also is done in the ‘excessive’ fashion of halting the narrative entirely for Henry to announce some insight, thereby also showing his mastery since it is as if he can control the film.

Soon after Karen has joined the mafia family, we see her at a wives’ gathering, where the women are described in her voice over as wearing too much make-up. However, when we look closely at the gathered women, it becomes clear (if not over-stated) that at least two of the wives are wearing make-up in order to cover up bruises and cuts that likely have been caused by beatings from their spouses.

In other words, we might consider make-up to be a form of excess, but really that ‘excess’ is here used as a way of masking damage in the form of bruising. What this in turn suggests to us is that the other excesses of the film – from the bling to the bravado camera movements – are also trying to hide over some form of damage or bruising, as Morrie tries to cover his otherwise bald pate.

But what is this damage/bruising?

In Tommy’s case, his excessive violence seems to be a standard little-man syndrome, as even he seems to suggest at one point during the story that leads to the ‘funny’ sequence (with Tommy’s storytelling and ‘funniness’ itself being a way of covering over his psychosis – and the film’s comedy as a whole being a way of covering over the psychosis of mafia life more generally). But Tommy’s little-man syndrome here also explains to us something that all of the other characters tend to carry, too: a refusal to be a ‘nobody’ but instead the desire to be a ‘somebody.’

In other words, it is the fact of having been born as a nobody that is the bruise that these gangsters wish to cover over.

There is more to it than this. When Henry betrays his ‘friends’ at the film’s end, he explains that only a Birth Certificate and a record of his previous imprisonment are what the government has on record about his existence. Earlier, when Henry begins to ditch school as a young hood, he says that he does not want to pledge allegiance to the flag or profess any ‘good government bullshit.’

In other words, it would seem that the damage that Henry wants to cover over is not simply being born a nobody, but being born a subject in America, which in turn is to be born a subject under capitalism, with the nation functioning as the structuring principle of the system.

A paradox: governments give to their subjects a name. Indeed, they give you a subjectivity. However, far from turning you into somebody, this assigned name confirms you as a nobody, since really the name functions as a form of what Louis Althusser would call ‘interpellation.’ That is, when the government calls your name, you respond, thereby affirming not your power, but the power of the government as you answer its call and respect its rules. Those with real power have no name (as Paulie perhaps understands in the film – always carrying out his business in secret). To be somebody, then, is paradoxically to have no name.

In this sense, excess – and the desire to show one’s wealth – is always the gangster’s undoing and why gangster films are always films about social climbers, or those who defy the power of the state and/or those in power – while power is really consolidated in hidden areas (even if Paulie does in the end die in jail). We do not know the names of the powerful.

(Read in this sense, Donald Trump is a gangster upstart – and we might even admire him for taking on the invisible corridors of power [represented by the Clintons?], were it not for the fact that Trump clearly does not seem invested in doing anything for anyone other than himself and his cronies. But like all gangsters, he is likely to come undone.)

Bearing in mind Henry’s avoidance of taxes and refusal to pledge allegiance to the flag, we can understand that the mafia (any mafia) functions as an alternative form of government. As Henry says, the mafia was simply protection – at least prior to its entry into the narcotics racket.

More than this, though, we can understand that the protection offered by a government, with taxes functioning as protection money, and with the government giving to its subjects a name (a birth certificate) and keeping tabs on them (police records) is really nothing other than a mafia. Governments are mafias; governments are the institutionalisation of gangsterism – as the Trump election perhaps clarifies.

Viewed in this light – that any national subject is really just a nobody paying protection money to a government that has convinced its subjects via interpellation that it is ‘good’ – it seems obvious that in order to become somebody, Henry will paradoxically go against his government, not pay his taxes, and in effect form his own republic.

More than this: as someone who will never quite be accepted into the mafia family on account of not being 100 per cent Italian, Henry will inevitably betray that family, too, since ultimately he works out that he is not really anything to them, either (they will kill him the minute he begins to get in their way).

It is a further paradox in the film that Henry must lose his identity as Henry Hill by entering into the witness protection programme. Ultimately, the government does get him – and his anonymous identity under witness protection confirms that the government does not care about its subjects, but it definitely wants to bury the competition by having the mafia bosses put away – as happens to Paulie and Jimmy.

And so Goodfellas shows us a world in which one is born a ‘nobody’ via being given a regular name. It then shows how to become somebody, one must rival government. In this process, though, one typically enters a world of excess – the need to show one’s power off and/or to cover over the bruises of being nobody. This allure of excess is one’s undoing, since it identifies one as a threat to all and every other person aspiring to power. Violence and comedy both ensue (as does violence as comedy), since rival powers will feel compelled to fight as long as power is perceived as unevenly distributed (the system of power is the institutionalisation of uneven distribution), and comedy will function as a way of covering over the bruises that cause the hunt for power and which also are caused by the lack of power.

Scorsese’s film does not just tell this story; it also embodies it with its own excesses – specifically trying to demonstrate that cinema is superior to/more powerful than television, with cinema thus being revealed as itself a key tool in the institutionalisation of power via consumerism (advertising and those who profit from it), the power of the media/cinema industry itself, and the sense that if you are not in a movie, then you are nobody.

(Even if the really powerful in the film industry are not the people whom we see – the stars – although these stars make bids for power on many occasions, but rather the unnamed people whom we never see. No wonder that at least one oppositional force has worked out that a potential way to rival governmental power is to be Anonymous. No wonder that show-offs with money in the UK are looked down upon by the quietly powerful as nouveau and gauche. No wonder that the storing of all data by government takes place as a means of precisely identifying who you are as a subject, in order that you continue to respect the power of government – cybernetics as, precisely, a form not of liberation but of government [both government and cybernetics have the same etymological roots])

There are many more things to discuss about Goodfellas, including its specifically masculine world – where women are in some senses part and parcel of the cinematic and excessive existence that these men desire (they want women, but not a woman who talks back/who tries to assert her power – with Henry’s demise being mapped from the start by his attraction to Karen when she upbraids him for standing her up, i.e. Henry is ‘weak’, a demise also signalled regularly by Henry’s lack of appetite for violence and so on).

There is also a racial dimension to the film, with the music equally playing an important role (perhaps it is telling that it is the second, piano-driven ‘movement’ of Derek and the Dominos’ ‘Layla’ that forms the film’s final theme – for this section of the song is also ‘excessive’ after the otherwise famous Eric Clapton guitar riff and singing that forms its first ‘movement’; notably the music also plays as we see Johnny Roastbeef and his girlfriend excessively murdered in the afore-mentioned pink cadillac, with the repetition of the song itself constituting some sort of ‘excessive’ use).

While a more complete reading of the film would look closely at these topics, however, I should like to end with two observations.

The first is that the name Goodfellas in some senses implies capitalist relationships, since the term ‘fellow’ means “one who puts down money with another in a joint venture.” That is, good fellows are ones who work with each other for money, and not for friendship.

(The film’s title differs from that of Nicholas Pileggi’s book from which the film is adapted, Wiseguys. The word ‘guy’ is derived from the same word as ‘guide’ – and by extension the Spanish term for a film script, guión. Wiseguys ‘see’ – whereas goodfellas invest. Perhaps the cinematic excess/cinema as excess of Scorsese’s film suggests how it, too, is trying to carve out an existence under the capitalist regime of filmmaking – getting away from the written form/script/guide/guión and into something different, a cinema of pure excess. Scorsese as gangster upstart filmmaker – with the arts clearly tolerating upstarts as a controlled form of excess, i.e. Scorsese is not really a threat to anyone, being much like a clown, the person who can speak truth to power and not get killed for it – obviously Tommy does not want to be a clown, since he does not want to speak truth to power; he wants power…)

Secondly, watching Goodfellas today, it is clear how closely Scorsese’s subsequent Wolf of Wall Street (USA, 2013) follows it as a guide – including various flourishes such as the lead character turning to camera and discussing what is going on. Indeed, it is almost as if The Wolf of Wall Street is a remake of Goodfellas transposed from the mafia and into the world of banking.

Two subsequent things can be observed from this parallel between Goodfellas and The Wolf…. Firstly, the rise of the mafia is more or less concurrent with the rise of investment banks in the 1970s and into the 1980s, a parallel that potentially alludes to the mafia-esque nature of banks (to which governments are beholden and not the other way around, as post-crisis bailouts would seem to suggest).

More than this: both the rise of the mafia and the rise of the banks are linked to the rise of the drug trade – as well as to media and the excesses of gambling. Gangsterism, banking, cinema, drugs, media: all are excesses, suggesting that the rise of neoliberal capital is precisely the rise of a world of excess in which to be a nobody is a humiliating failure and all will humiliate themselves in order to be a somebody. This striving for excess is ultimately a control mechanism to keep everyone consuming, thereby maintaining the power of those ‘invisible people’ who already hold it.

Goodfellas uses comedy to critique this world, with Scorsese emerging perhaps as the ‘King of Comedy’ through his ability to laugh at even the most sick violence. The comedy is done through Scorsese using excess against itself.

An ambivalence arises between critiquing and indulging cinema’s tendency towards excess, and this ambivalence is a rich vein that Scorsese has long since mined. May he continue to do so – even if this means that he is perhaps more complicit with capital than critical of it… Unless like Henry, Scorsese, too, is getting to the heart of capital in order ultimately to betray it and to put it behind bars.

* Note added 17 January 2019: it strikes me that when the camera tracks in on the Christmas tree and the bauble, the shot is in fact a reference by Scorsese to Luchino Visconti’s Ludwig (Italy/France/West Germany, 1973), which thanks to MUBI I saw early in 2019. Visconti’s film, which tells the tale of the excessive life of ‘mad’ King Ludwig of Bavaria (Helmut Berger), is equally excessive in style (lavish décors) and duration (just shy of four hours). And it also features a shot that cranes in on a Christmas tree that is decorated also by baubles, etc. In Visconti’s film, excess is equated with madness. Perhaps Scorsese also is suggesting that the propensity for excess is a sort of American madness. (Liotta as Henry seems to deliver a performance that at times, in its effeteness, seems not too far from that of Berger as Ludwig.)

The comedy of experimental cinema

American cinema, Blogpost, Canadian cinema, Experimental Cinema, Film reviews, UncategorizedI can only say what I saw and heard (and felt and thought).

Over the last two evenings, I have attended two experimental film events. The first was a screening of Michael Snow’s La région centrale (Canada, 1971) at the Serpentine Gallery, which screened alongside the opening credits of Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1958) – with both being chosen by artist Lucy Raven, whose solo exhibition, Edge of Tomorrow, is currently on there. The second was a performance at Tate Modern of Tony Conrad’s 55 Years on the Infinite Plain (originally called 10 Years on the Infinite Plain when first performed in New York, USA, in 1972, and which has been growing in age ever since – now beyond Conrad’s death last year).

For those unfamiliar with either of these works, the former is a three-hour film shot on the top of a mountain in Québec, and which features images captured remotely by Snow using a robotic arm, to which Snow’s camera was attached, and which rotates in a long series of different directions. The latter is a 90-minute piece featuring ‘drone’ music and black and white strips that flicker on a screen from four projectors simultaneously.

Both experiences involve a fair amount of discomfort, not least because traditional cinema seats were not provided, with the viewer instead having to sit on a wooden stand (La région centrale) or on the floor (55 Years…). Standing is an option. But either way, one really feels the presence of one’s body as one tries to find comfort during the screenings (and live musical performance in the case of 55 Years…).

I am not an expert on experimental cinema. I have seen a fair amount, read a fair amount of literature about it, and also think about it (and occasionally write about experimental aspects of cinema that is otherwise not so overtly non-narrative as these two films).

I am driven to write about these back-to-back experiences, though, not simply to expose my ignorance of the subject (I can’t imagine that I shall say much that others have not written – or certainly thought – in relation to these films), but to convey some thoughts that I had while watching the films. Perhaps that is, after all, one of the things that a blog can do.

To get to my thoughts, though, we must describe what happens in the films. As I have already hinted, ‘not much happens’ from the perspective of someone looking for a film that tells a story. La région centrale features images captured by the camera as it moves round and round, back and forth, spinning upside down, moving in circles in all sorts of directions and more.

55 Years…, meanwhile, features a deep electric bass line (performed on this occasion by Dominic Lash), accompanied by violin (Angharad Davies) and long string drone (Rhys Chatham). At first one projector, then two, then three, then four fill the wide screen with the flickering lines, before all four projectors slowly begin to converge, their images overlapping, and then are turned off one by one, until only one flickering image remains.

Probably sounds pointless, maybe even dull, right – especially if one lasts 180 minutes and the other 90?

I do not think so. Indeed, quite the opposite.

The Snow experience induced in me so many different thoughts, which perhaps have at their core a sense of seeing the Earth as if through the eyes of an alien. Initially surveying the ground, the camera then begins to rotate in such ways that we are consistently being given new perspectives on our world – toying with it, twisting it, turning it, experimenting with it.

As María Palacios Cruz explained in her introduction, Snow deliberately tried to find a spot in his native Canada where no visible trace of human life could be seen (something that might recall my earlier post about the ‘American eye’ in relation to Le corbeau). In other words, he absolutely wants us to see the world from an inhuman perspective; to see the world ‘for itself.’

In the process, we begin to understand how as humans we often do not see the world ‘for itself’ but how it is ‘for us’ (and this is not necessarily a bad thing; we are driven to live and survive by our selfish genes, after all). By getting us to see the world ‘for itself,’ the world itself is made ‘alien’ to us, or we see the world as if through alien eyes. The film becomes a panoply of different ways to look at the world through the insistent movement of the camera – with the non-stop nature of that camera movement also bringing to mind the way in which our relatively static perspective of the world is perhaps key in bringing about our inability to see the world ‘for itself.’

For, the world is also movement – but generally we do not have eyes to see it. The rhythms of the world are perhaps too slow for us to detect. What Snow’s film does, then, is to bring to mind those rhythms. Not just Snow’s film, but by extension cinema as a whole is thus in part a machine to present to us something like ‘deep time’ – the long, slow rhythms of the world that extend further back than we can remember and further into the future than we can imagine (in other words, a world without humans). Perhaps this is why a narrative classic like Vertigo is also chosen to play in part alongside Snow’s film.

If Snow’s film takes us into the realm of planetary time, Conrad’s film takes us (or me, at least) into the realm of universal time.

Using black and whites strips alone, Conrad takes us into a realm whereby I am confronted not just with a world that exists far beyond the human realm, but with the way in which the world – the universe itself – comes into and out of being. If the world pre-existed humans by billions of years, and if it will outlive humans by billions of years (La région centrale), then Conrad’s film tells us that the universe pre-existed the world by trillions of years, and will continue to exist after the world has gone by trillions of years. (It exists beyond time itself, and beyond measure. Again, language becomes meaningless.)

More than this… 55 Years on the Infinite Plain tells us – in its flickering of white, or being, and black, or nothing – that existence itself comes into and out of being. That there is a beyond existence; that there is a beyond being; that there is a beyond ‘is’ – such that one cannot even express what we are describing since to say that ‘there is a beyond “is”‘ is clearly a contradiction in terms (how can not-is and is co-exist?)!

If language cannot suffice for the task of explaining what we see, then we enter into the realm of experience and of a new, different kind of thought (that also cannot be defined simply by what we ‘see,’ since it must be experienced, too).

What is the universe? But simply a flicker of light in an otherwise infinite blackness.

If 55 Years… takes us somehow beyond the universe, then it takes us into a realm not of a singular reality (a uni-verse), but into the realm of multiple realities. An alien perspective, or what philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy and physicist Aurélien Barrau might suggest is the necessary understanding that there is no world, but only multiple, infinite worlds.

As per the translation of their book on the matter: what is these worlds coming to? What these worlds is coming to (note the grammatical error; again, language does not quite suffice) is the co-existence of existence and non-existence. To invoke a different philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre, being and nothingness at the same time.

Am I being pretentious? Possibly. I mean, people walked out of both screenings – and so clearly not everyone goes with these films. But at the end of 55 Years… the remaining audience members (perhaps as many as 100 people) sat in silence and darkness for about a minute. Finally, some applause – enthusiastic applause, some whoops of joy. Clearly they needed a moment to catch their thoughts, because this film had taken them somewhere different, somewhere special.

In other words, if to someone who was not there this all sounds like wank, to the majority of people who were there, this meant something – even if expressing it is and perhaps remains difficult. “That was absolutely fucking amazing,” said the woman sat next to me. I felt like dancing (and did nearly throughout 55 Years… – although I refrained from doing so).

Elsewhere I have written about how Hollywood presents to us narrative films that, even if they contain ‘puzzles’ for us to work out (my example is Inception, Christopher Nolan, USA/UK, 2010), they are still designed to be easy to consume and, by extension, not particularly challenging. I then suggest that films that do not involve narratives (my example is Five Dedicated to Ozu, Iran/Japan/France, 2003, by the late Abbas Kiarostami) can be quite challenging, even if there is no specific puzzle to work out – as we just see images of waves lapping the shore, or ducks walking along a beach, or a pond at night.

My argument in that essay is that common responses to Five… might include either ‘I got it after two minutes, so I do not know why I had to sit through that’ or ‘I did not get it’ – while people might easily say that they ‘got’ Inception (even though it is more than twice the length of Five…).

I suggest that there is not so much anything to ‘get’ with Five… (or Inception, or Vertigo – as its inclusion by Lucy Raven in her programme makes clear), but that one might ‘get into’ that sort of film by working at being an attentive audience member and beginning to marvel at what a wave lapping against the shore is and might mean (is it not a miracle that this happens?) as opposed only to marvelling at special effects and ‘mind-bending ideas’ (even though the leaders of the two largest energy companies in the world sit next to each other on an aeroplane and do not recognise each other).

(Besides which, whenever one says that one ‘got’ such a film after two minutes, they clearly do not ‘get’ it since part of getting it must involve experiencing the film in its entire duration, including the sense of slowness, and the different time or tempo of the piece. To demand that it be shorter is not to respect this otherness, but to apply one’s own rhythm to it, to curtail it, perhaps even to kill it.)

(Speaking of marvelling, I also found myself marvelling during 55 Years… about the fact that I can rotate my head. How is it possible that a human evolved from the mud of a planet that itself was a rock spewed from a star, such that it has a head that can rotate on a joint that sits atop a backbone and which contains eyes that can see and ears that can hear?)

To return from these loco parentheses: I make reference to my own essay not simply to continue to explain to a(n imagined?) ‘viewer-on-the-street’ that these non-narrative films might do something for us (and that thus people who might otherwise never go to watch such films might do worse than to give them a try), but also to correct what I wrote in that essay.

In that essay, I wrote that we might ‘get into’ films like Five Dedicated to Ozu by putting in some effort ourselves (rather than having nigh everything served up to us on a plate, as per Inception). However, now I think it would be better to suggest that we do not ‘get into’ but that we ‘get with’ such films (which is not necessarily to the exclusion of ‘getting with’ mainstream films; I believe that we can get with cinema as a whole – but don’t think that we should only get with the mainstream at the expense of the weird and the wonderful).

Why do I now want to say that we should ‘get with’ as opposed to ‘get into’ these films?

Well, in part this is to explain that getting a bit ‘pretentious’ (talking about cosmic things like a world without humans and a multiverse that exists and does not) is to get with what these films are doing, or at the very least what these films can do with us (it might also be an act of love if we were to say that we ‘go with’ these films – since coitus itself means to go with [co-itus] – as I have suggested here).

Furthermore, the preposition ‘with’ (a favourite of Jean-Luc Nancy) suggests not quite a disconnection from the world (seeing it through alien eyes), but also a connection with the world (seeing it ‘for itself’ – or from the perspective of a world that has seen so much more than humans and a multiverse that has seen so much more than our world).

Seeing through the eyes of the other, a kind of forgetting oneself, is also to commune with another – and in this case not just another human, but a whole other timescale (the entirety of existence) and space scale (a planet, a universe – as well, in the case of La région centrale when it shows us the land beneath the camera in close up, a rock, a patch of earth, a blade of grass). ‘With’ is to go beyond the self, to open the self up not only to the other human, but in the cases of La région centrale and 55 Years on the Infinite Plain, the inhuman.

Furthermore, ‘with’ always implies plurality, or a multiplicity of things and perspectives. For, one cannot be with anything or anyone if there is no thing or one beyond the self with which to be. With, therefore, suggests that we live in a multiverse, and that what these worlds is coming to is perhaps us, our understanding of the multiverse, and our place with it.

(The Conrad also suggests with in other ways – particularly the way in which my eyes when they move from left to right can make the flickers seem as though moving in that direction – before then moving in the other direction as my eyes move from right to left… That is, I am with the film in the sense that I co-create what I see; I see not just a different perspective, but a different perspective with my own eyes; I am entangled with the multiverse. This might seem to contradict the idea that I get beyond myself – but what perhaps really is exposed is not just the world beyond the self, but also the relationship between that world beyond self, and the self itself. What is exposed or revealed is our withness – and how the otherness of that with which we are is necessary for me even to exist and to have my sense of self/my perspective in the first place.)

I wish to end, then, by suggesting that these films do not just put us with the universe or multiverse. They put us with the medium of cinema, too, which opens us up to these new perspectives. I hear the 16mm projector rattle along during La région centrale, and I turn to see the projectors during 55 Years…. The experience of these two films is, then, to be with media, to be co-media, to be comedy.

What we can experience during these films is thus the comedy of the multiverse. When we find such films frustrating, we are perhaps taking them far too seriously (I personally found myself laughing regularly during both films as I marvelled at the possibility of anything existing at all). When we are serious, it is because we are rigid in our ways, in our thinking, and we are resistant to change. We do not become, we are not coming to, we are not with (perhaps we are solipsistically dreaming, a state of unconsciousness from which we can recover only by ‘coming to’).

To be less serious, to enjoy the comedy: this is not only a route to laughter and thus by extension happiness – it is perhaps also a route via with to wisdom (to be ‘other-wise’).

Long live experimental cinema. When screenings like these come along, I can only recommend one thing: get with it.

Arrival (Denis Villeneuve, USA, 2016)

American cinema, Blogpost, UncategorizedOnly some brief notes, including **spoilers**, owing to a lack of time…

Arrival tells the story of linguist Louise Banks (Amy Adams) who, with physicist Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner), is charged with establishing contact with aliens who have arrived on Earth.

Banks opens the film by asking a question to her class about Portuguese – why is it so strangely spoken given the location of that country? In Portuguese, it is common to refer to another human being as a cara, which literally means ‘face,’ although it also has a sense of ‘dear’. In other words, all humans have a face, and all humans are dear – no matter where they come from, who they are, or how long they live.

When Banks et al approach the aliens, spatial orientation is warped: sideways is upside down is the right way up. The aliens appear from behind a giant white screen, clearly of the dimensions of the contemporary widescreen cinema screen. That Banks and Donnelly are really talking to cinema is made clear by the fact that Donnelly dubs the two aliens whom they encounter Abbott and Costello: they are really just cinema talking back to humans.

The language of the aliens demonstrates a nonlinear conception of time: the aliens (shades of the Tralfamadorians from Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five) perceive all time at once. It is perceiving all of time at once that Banks will learn is the key to understanding the aliens who, as per Interstellar (Christopher Nolan, USA/UK, 2014), are basically here to help us.

The aliens are here to help us by giving to us their language, or rather their understanding of time.

In a world in which linear time becomes ‘meaningless,’ the distinction between life and death also becomes meaningless. That is, we know that we will die – and in the case of Banks, this means knowing that her future daughter will die of a rare disease and that she can do nothing about it.

Nonetheless, what Banks learns is to embrace this destiny and to give life to her daughter (although this will lead to a split between her and the daughter’s father, who will be Donnelly). Why? Because while we might fear death, it is worse that we should fear life, no matter how transient.

However, there are further extrapolations to make here.

When the spaceships leave, they in effect disappear, or dematerialise.

It is as if the aliens simply flip into the dimension of reality with which humans are most familiar, only to flip out again.

What this tells us, beyond the life that is Banks’ daughter, is that all matter – perhaps including all antimatter (that which exists, but not in the human dimension) is alive, or has the potential for life. All matter has a face. All matter is a cara. All matter is dear.

There is confusion in the film regarding the use of the word weapon. Might it really mean tool? Might it mean something else?

It is disclosed that the weapon that the aliens give to humans is their language, their nonlinear conception of time, which, in allowing humans to see life everywhere in principle brings about world peace.

Why does it do this?

It does this because in recognising that all matter is alive, in recognising that everything is dear, or has value, then it becomes the role of humans all to become woman, or more pertinently to become mother. A literal mother in Banks’ case. But a mother to all matter. To nurture the world and the universe by extension. To take care/cara of the world.

Where humanity has gone wrong is precisely in the concept of the weapon. For, while the give to us a language, it might be that this language is a weapon. However, what this ‘weapon’ really is, is a gift.

This is important for Banks. Because while we hear about/see the traumatic (future) loss of her daughter, she is also working through the fact that some Farsi translations that she did for the US government led to the deaths of various people – as she off-handedly remarks to Colonel Weber (Forest Whitaker) at her point of recruitment.

In other words (not unlike Harry Caul, played by Gene Hackman, who is working through the deaths of various people whose schemes he exposed in The Conversation, Francis Ford Coppola, USA, 1974), Banks is dealing with the trauma of having used language as a weapon and not as a gift. Or, put differently, of using information as a weapon, rather than realising information as a gift.

When information is a weapon, then only some things are dear/cara/have a face, and the rest is discardable, expendable, can be killed. When information is understood as a gift, then we can come to see not that some things are dear, but that all things are dear – that value is evenly spread across the universe and across time, including the virtual time of when matter spins out into antimatter/different dimensions, before spinning back into the material world of the human dimension. Everything has a face.

So… if the aliens are really cinema, then what Arrival suggests is that cinema’s chief gift is to show us universal life and universal time, even the time of the virtual (that which does not exist, parallel dimensions and so on). Cinema is alien. Cinema is intelligent. Cinema is alive. Linear time is an illusion. Is is an illusion. The becoming of the universe is life.

Adventures in Cinema 2015

African cinema, American cinema, Blogpost, British cinema, Canadian cinema, Chinese cinema, Documentary, European cinema, Film education, Film reviews, French Cinema, Iranian cinema, Italian Cinema, Japanese Cinema, Latin American cinema, Philippine cinema, Ritzy introductions, Transnational Cinema, Ukrainian Cinema, UncategorizedThere’ll be some stories below, so this is not just dry analysis of films I saw this year. But it is that, too. Sorry if this is boring. But you can go by the section headings to see if any of this post is of interest to you.

The Basics

In 2015, I saw 336 films for the first time. There is a complete list at the bottom of this blog. Some might provoke surprise, begging for example how I had not seen those films (in their entirety) before – Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, France/UK, 1985) being perhaps the main case in point. But there we go. One sees films (in their entirety – I’d seen bits of Shoah before) when and as one can…

Of the 336 films, I saw:-

181 in the cinema (6 in 3D)

98 online (mainly on MUBI, with some on YouTube, DAFilms and other sites)

36 on DVD/file

20 on aeroplanes

1 on TV

Films I liked

I am going to mention here new films, mainly those seen at the cinema – but some of which I saw online for various reasons (e.g. when sent an online screener for the purposes of reviewing or doing an introduction to that film, generally at the Ritzy Cinema in Brixton, London).

And then I’ll mention some old films that I enjoyed – but this time only at the cinema.

Here’s my Top 11 (vaguely in order)

- Clouds of Sils Maria (Olivier Assayas, France/Germany/Switzerland, 2014)

- El Botón de nácar/The Pearl Button (Patricio Guzmán, France/Spain/Chile/Switzerland, 2015)

- Eisenstein in Guanajuato (Peter Greenaway, Netherlands/Mexico/Finland/Belgium/France, 2015)

- Bande de filles/Girlhood (Céline Sciamma, France, 2014)

- Timbuktu (Abderrahmane Sissako, France/Mauritania, 2014)

- Saul fia/Son of Saul (László Nemes, Hungary, 2015)

- 45 Years (Andrew Haigh, UK, 2015)

- Force majeure/Turist (Ruben Östlund, Sweden/France/Norway/Denmark, 2014)

- The Thoughts Once We Had (Thom Andersen, USA, 2015)

- Phoenix (Christian Petzold, Germany/Poland, 2014)

- Mommy (Xavier Dolan, Canada, 2014)

And here are some proxime accessunt (in no particular order):-

Enemy (Denis Villeneuve, Canada/Spain/France, 2013); Whiplash (Damien Chazelle, USA, 2014); Inherent Vice (Paul Thomas Anderson, USA, 2014); Jupiter Ascending (Andy and Lana Wachowski, USA/Australia, 2015); The Duke of Burgundy (Peter Strickland, UK/Hungary, 2014); Catch Me Daddy (Daniel Wolfe, UK, 2014); White God/Fehér isten (Kornél Mundruczó, Hungary/Germany/Sweden, 2014); Dear White People (Justin Simien, USA, 2014); The Falling (Carol Morley, UK, 2014); The Tribe/Plemya (Miroslav Slaboshpitsky, Ukraine/Netherlands, 2014); Set Fire to the Stars (Andy Goddard, UK, 2014); Spy (Paul Feig, USA, 2015); Black Coal, Thin Ice/Bai ri yan huo (Yiao Dinan, China, 2014); Listen Up, Philip (Alex Ross Perry, USA/Greece, 2014); Magic Mike XXL (Gregory Jacobs, USA, 2015); The New Hope (William Brown, UK, 2015); The Overnight (Patrick Brice, USA, 2015); Trois souvenirs de ma jeunesse/My Golden Days (Arnaud Desplechin, France, 2015); Manglehorn (David Gordon Green, USA, 2014); Diary of a Teenage Girl (Marielle Heller, USA, 2015); Hard to be a God/Trudno byt bogom (Aleksey German, Russia, 2013); Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation (Christopher McQuarrie, USA, 2015); Trainwreck (Judd Apatow, USA, 2015); Mistress America (Noah Baumbach, USA/Brazil, 2015); While We’re Young (Noah Baumbach, USA, 2014); Marfa Girl (Larry Clark, USA, 2012); La Sapienza (Eugène Green, France/Italy, 2014); La última película (Raya Martin and Mark Peranson, Mexico/Denmark/Canada/Philippines/Greece, 2013); Lake Los Angeles (Mike Ott, USA/Greece, 2014); Pasolini (Abel Ferrara, France/Belgium/Italy, 2014); Taxi Tehran/Taxi (Jafar Panahi, Iran, 2015); No Home Movie (Chantal Akerman, Belgium/France, 2015); Dope (Rick Famuyiwa, USA, 2015); Umimachi Diary/Our Little Sister (Kore-eda Hirokazu, Japan, 2015); Tangerine (Sean Baker, USA, 2015); Carol (Todd Haynes, UK/USA, 2015); Joy (David O. Russell, USA, 2015); PK (Rajkumar Hirani, India, 2014); Eastern Boys (Robin Campillo, France, 2013); Selma (Ava DuVernay, UK/USA, 2014); The Dark Horse (James Napier Robertson, New Zealand, 2014); Hippocrate/Hippocrates: Diary of a French Doctor (Thomas Lilti, France, 2014); 99 Homes (Ramin Bahrani, USA, 2014).

Note that there are some quite big films in the above; I think the latest Mission: Impossible topped James Bond and the other franchises in 2015 – maybe because McQuarrie is such a gifted writer. Spy was for me a very funny film. I am still reeling from Cliff Curtis’ performance in The Dark Horse. Most people likely will think Jupiter Ascending crap; I think the Wachowskis continue to have a ‘queer’ sensibility that makes their work always pretty interesting. And yes, I did put one of my own films in that list. The New Hope is the best Star Wars-themed film to have come out in 2015 – although I did enjoy the J.J. Abrams film quite a lot (but have not listed it above since it’s had enough attention).

Without wishing intentionally to separate them off from the fiction films, nonetheless here are some documentaries/essay-films that I similarly enjoyed at the cinema this year:-

The Wolfpack (Crystal Moselle, USA, 2015); National Gallery (Frederick Wiseman, France/USA/UK, 2014); Life May Be (Mark Cousins and Mania Akbari, UK/Iran, 2014); Detropia (Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady, USA, 2012); Storm Children: Book One/Mga anak ng unos (Lav Diaz, Philippines, 2014); We Are Many (Amir Amirani, UK, 2014); The Salt of the Earth (Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, France/Brazil/Italy, 2014).

And here are my highlights of old films that I managed to catch at the cinema and loved immensely:-

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis/Il Giardino dei Finzi Contini (Vittorio de Sica, Italy/West Germany, 1970); Il Gattopardo/The Leopard (Lucchino Visconti, Italy/France, 1963); Images of the World and the Inscriptions of War/Bilder der Welt und Inschrift des Krieges (Harun Farocki, West Germany, 1989); A Woman Under the Influence (John Cassavetes, USA, 1974).

With two films, Michael Fassbender does not fare too well in the below list – although that most of them are British makes me suspect that the films named feature because I have a more vested stake in them, hence my greater sense of disappointment. So, here are a few films that got some hoo-ha from critics and in the media and which I ‘just didn’t get’ (which is not far from saying that I did not particularly like them):-

La Giovinezza/Youth (Paolo Sorrentino, Italy/France/Switzerland/UK, 2015), Sunset Song (Terence Davies, UK/Luxembourg, 2015); Macbeth (Justin Kurzel, UK/France/USA, 2015); Love & Mercy (Bill Pohlad, USA, 2014); Slow West (John Maclean, UK/New Zealand, 2015); Tale of Tales/Il racconto dei racconti (Matteo Garrone, Italy/France/UK, 2015); Amy (Asif Kapadia, UK/USA, 2015).

And even though many of these feature actors that I really like, and a few are made by directors whom I generally like, here are some films that in 2015 I kind of actively disliked (which I never really like admitting):-

Hinterland (Harry Macqueen, UK, 2015); Fantastic Four (Josh Trank, USA/Germany/UK/Canada, 2015); Pixels (Chris Columbus, USA/China/Canada, 2015); Irrational Man (Woody Allen, USA, 2015); Aloha (Cameron Crowe, USA, 2015); Point Break 3D (Ericson Core, Germany/China/USA, 2015); American Sniper (Clint Eastwood, USA, 2014); Every Thing Will Be Fine 3D (Wim Wenders, Germany/Canada/France/Sweden/Norway, 2015).

Every Thing Will Be Fine struck me as the most pointless 3D film I have yet seen – even though I think Wenders uses the form excellently when in documentary mode. The Point Break remake, meanwhile, did indeed break the point of its own making, rendering it a pointless break (and this in spite of liking Édgar Ramírez).

Where I saw the films

This bit isn’t going to be a list of cinemas where I saw films. Rather, I want simply to say that clearly my consumption of films online is increasing – with the absolute vast majority of these seen on subscription/payment websites (MUBI, DAFilms, YouTube). So really I just want to write a note about MUBI.

MUBI was great a couple of years ago; you could watch anything in their catalogue when you wanted to. Then they switched to showing only 30 films at a time, each for 30 days. And for the first year or so of this, the choice of films was a bit rubbish, in that it’d be stuff like Battleship Potemkin/Bronenosets Potemkin (Sergei M Eisenstein, USSR, 1925). Nothing against Potemkin; it’s a classic that everyone should watch. But it’s also a kind of ‘entry level’ movie for cinephiles, and, well, I’ve already seen it loads of times, and so while I continued to subscribe, MUBI sort of lost my interest.

However, this year I think that they have really picked up. They’ve regularly been showing stuff by Peter Tscherkassky, for example, while it is through MUBI that I have gotten to know the work of American artist Eric Baudelaire (his Letters to Max, France, 2014, is in particular worth seeing). Indeed, it is through Baudelaire that I also have come to discover more about Japanese revolutionary filmmaker Masao Adachi, also the subject of the Philippe Grandrieux film listed at the bottom and which I saw on DAFilms.

MUBI has even managed to get some premieres, screening London Film Festival choices like Parabellum (Lukas Valenta Rinner, Argentina/Austria/Uruguay, 2015) at the same time as the festival and before a theatrical release anywhere else, while also commissioning its own work, such as Paul Thomas Anderson’s documentary Junun (USA, 2015). It also is the only place to screen festival-winning films like Història de la meva mort/Story of my Death (Albert Serra, Spain/France/Romania, 2013) – which speaks as much of the sad state of UK theatrical distribution/exhibition (not enough people are interested in the film that won at the Locarno Film Festival for any distributors/exhibitors to touch it) as it does of how the online world is becoming a viable and real alternative distribution/exhibition venue. Getting films like these is making MUBI increasingly the best online site for art house movies.

That said, I have benefitted from travelling a lot this year and have seen what the MUBI selections are like in places as diverse as France, Italy, Hungary, Mexico, China, Canada and the USA. And I can quite happily say that the choice of films on MUBI in the UK is easily the worst out of every single one of these countries. Right now, for example, the majority of the films are pretty mainstream stuff that most film fans will have seen (not even obscure work by Quentin Tarantino, Woody Allen, Jean-Luc Godard, Fritz Lang, Terry Gilliam, Robert Zemeckis, Frank Capra, Guy Ritchie, Steven Spielberg, Alejandro González Iñárritu, Wes Anderson). Indeed, these are all readily available on DVD. More unusual films like Foreign Parts (Verena Paravel and J.P. Sniadecki, USA/France, 2010) are for me definitely the way for MUBI to go – even in a country that generally seems as unadventurous in its filmgoing as this one (the UK).

I’ve written in La Furia Umana about the changing landscape of London’s cinemas; no need to repeat myself (even though that essay is not available online, for which apologies). But I would like to say that while I have not been very good traditionally in going to Indian movies (which regularly get screened at VUE cinemas, for example), I have enjoyed how the Odeon Panton Street now regularly screens mainstream Chinese films. For this reason, I’ve seen relatively interesting fare such as Mr Six/Lao pao er (Hu Guan, China, 2015). In fact, the latter was the last film that I saw in 2015, and I watched it with maybe 100 Chinese audience members in the heart of London; that experience – when and how they laughed, the comings and goings, the chatter, the use of phones during the film – was as, if not more, interesting as/than the film itself.

Patterns

This bit is probably only a list of people whose work I have consistently seen this year, leading on from the Tscherkassky and Baudelaire mentions above. As per 2015, I continue to try to watch movies by Khavn de la Cruz and Giuseppe Andrews with some regularity – and the ones that I have caught in 2015 have caused as much enjoyment as their work did in 2014.

I was enchanted especially by the writing in Alex Ross Perry’s Listen Up, Philip, and then I also managed to see Ross Perry acting in La última película, where he has a leading role with Gabino Rodríguez. This led me to Ross Perry’s earlier Color Wheel (USA, 2011), which is also well worth watching.

As for Rodríguez, he is also the star of the two Nicolás Pereda films that I managed to catch online this year, namely ¿Dónde están sus historias?/Where are their Stories? (Mexico/Canada, 2007) and Juntos/Together (Mexico/Canada, 2009). I am looking forward to seeing more Rodríguez and Pereda when I can.

To return to Listen Up, Philip, it does also feature a powerhouse performance from Jason Schwartzman, who also was very funny in 2015 in The Overnight. More Schwartzman, please.

Noah Baumbach is also getting things out regularly, and I like Adam Driver. I think also that the ongoing and hopefully permanent trend of female-led comedies continues to yield immense pleasures (I am thinking of Spy, Mistress America, Trainwreck, as well as films like Appropriate Behaviour, Desiree Akhavan, UK, 2014, to lead on from last year’s Obvious Child, Gillian Robespierre, USA, 2014; I hope shortly to make good on having missed Sisters, Jason Moore, USA, 2015).

I don’t know if it’s just my perception, but films like Selma, Dear White People, Dope and more also seem to suggest a welcome and hopefully permanent increase in films dealing with issues of race in engaging and smart ways. It’s a shame that Spike Lee’s Chi-Raq (USA, 2015) may take some time to get over here. I am intrigued by Creed (Ryan Coogler, USA, 2015). I was disappointed that Top Five (Chris Rock, USA, 2014) only got a really limited UK release, too. Another one that I missed and would like to have seen.

Matt Damon is the rich man’s Jesse Plemons.

Finally, I’ve been managing to watch more and more of Agnès Varda and the late Chantal Akerman’s back catalogues. And they are both magical. I also watched a few Eric Rohmer and Yasujiro Ozu films this year, the former at the BFI Rohmer season in early 2015, the latter on YouTube (where the older films can roam copyright free).

Michael Kohler

During a visit to Hartlepool in 2015 to see my good friend Jenni Yuill, she handed me a letter that she had found in a first edition of a Christopher Isherwood novel. She had given the novel to a friend, but kept the letter. The letter was written by someone called Michael and to a woman who clearly had been some kind of mentor to him.

In the letter, Michael described some filmmaking that he had done. And from the description – large scale props and the like – this did not seem to be a zero-budget film of the kind that I make, but rather an expensive film.

After some online research, I discovered that the filmmaker in question was/is British experimental filmmaker Michael Kohler, some of whose films screened at the London Film Festival and other places in the 1970s through the early 1990s.

I tracked Michael down to his home in Scotland – and since then we have spoken on the phone, met in person a couple of times, and he has graciously sent me copies of two of his feature films, Cabiri and The Experiencer (neither of which has IMDb listings).

Both are extraordinary and fascinating works, clearly influenced by psychoanalytic and esoteric ideas, with strange rituals, dances, symbolism, connections with the elements and so on.

Furthermore, Michael Kohler is an exceedingly decent man, who made Cabiri over the course of living with the Samburu people in Kenya for a decade or so (he also made theatre in the communes of Berlin in the 1960s, if my recall is good). He continues to spend roughly half of his time with the Samburu in Kenya.

He is perhaps a subject worthy of a portrait film himself. Maybe one day I shall get to make it.

And beyond cinema

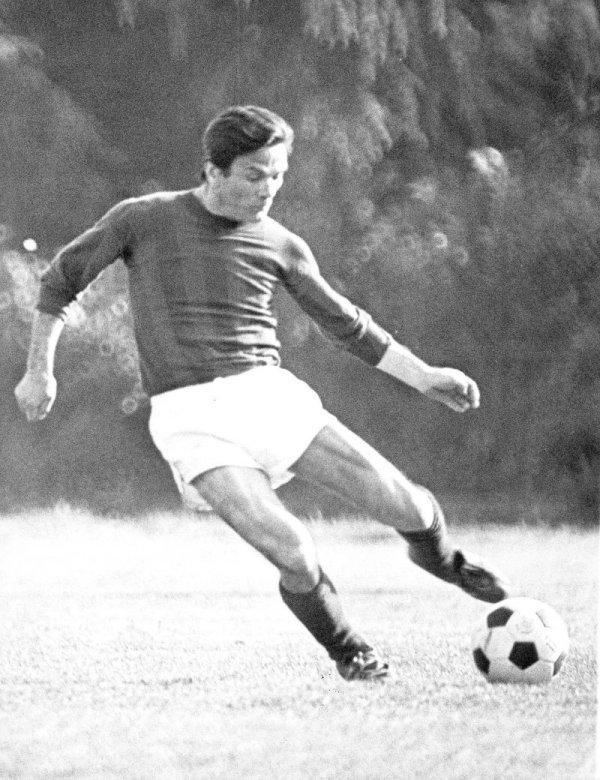

I just want briefly to say how one of the most affecting things that I think I saw this year was a photograph of Pier Paolo Pasolini playing football – placed on Facebook by Girish Shambu or someone of that ilk (a real cinephile who makes me feel like an impostor).

Here’s the photo:

I mention this simply because I see in the image some real joy on PPP’s part. I often feel bad for being who I am, and believe that my frailties, which are deep and many, simply anger people. (By frailties, I perhaps more meaningfully could say tendencies that run contrary to mainstream thinking and behaviours – not that I am a massive rebel or anything.) And because these tendencies run contrary to mainstream thinking and behaviours, I tend to feel bad about myself, worried that others will dislike me.

(What is more, my job does not help. I often feel that the academic industry is not so much about the exchange of ideas as an excuse for people to bully each other, or at least to make them feel bad for not being good enough as a human being as we get rated on absolutely everything that we do – in the name of a self-proclaimed and fallacious appeal to an absence of partiality.)

I can’t quite put it in words. But – with Ferrara’s Pasolini film and my thoughts of his life and work also in my mind alongside this image – this photo kind of makes me feel that it’s okay for me to be myself. Pasolini met a terrible fate, but he lived as he did and played football with joy. And people remember him fondly now. And so if I cannot be as good a cinephile or scholar as Girish Shambu and if no one wants to hear my thoughts or watch my films, and if who I am angers some people, we can still take pleasure in taking part, in playing – like Pasolini playing football. And – narcissistic thought though this is – maybe people will smile when thinking about me when I’m dead. Even writing this (I think about the possibility of people remembering me after I am dead; I compare myself to the great Pier Paolo Pasolini) doesn’t make me seem that good a person (I am vain, narcissistic, delusional); but I try to be honest.

And, finally, I’d like to note that while I do include in the list below some short films, I do not include in this list some very real films that have brought me immense joy over the past year, in particular ones from friends: videos from a wedding by Andrew Slater, David H. Fleming cycling around Ningbo in China, videos of my niece Ariadne by my sister Alexandra Bullen.

In a lot of ways, these, too, are among my films of the year, only they don’t have a name, their authors are not well known, and they circulate to single-figure audiences on WhatsApp, or perhaps a few more on Facebook. And yet for me such films (like the cat films of which I also am fond – including ones of kitties like Mia and Mieke, who own Anna Backman Rogers and Leshu Torchin respectively) are very much equally a part of my/the contemporary cinema ecology. I’d like to find a way more officially to recognise this – to put Mira Fleming testing out the tuktuk with Phaedra and Dave and Annette Encounters a Cat on Chelverton Road on the list alongside Clouds of Sils Maria. This would explode list-making entirely. But that also sounds like a lot of fun.

Here’s to a wonderful 2016!

COMPLETE LIST OF FILMS I SAW FOR THE FIRST TIME 2015

KEY: no marking = saw at cinema; ^ = saw on DVD/file; * = saw online/streaming; + = saw on an aeroplane; ” = saw on TV.

Paddington

The Theory of Everything

Le signe du lion (Rohmer)

Exodus: Gods and Kings

Enemy

Au bonheur des dames (Duvivier)

Il Gattopardo

Daybreak/Aurora (Adolfo Alix Jr)^

Eastern Boys

The Masseur (Brillante Mendoza)^

Stations of the Cross

Foxcatcher

National Gallery

Whiplash

American Sniper

Minoes

Fay Grim^

Tak3n

Tokyo Chorus (Ozu)*

Kinatay (Brillante Mendoza)^

Wild (Jean-Marc Vallée)

La prochaine fois je viserai le coeur

Pressure (Horace Ové)

La Maison de la Radio

L’amour, l’après-midi (Rohmer)

The Boxtrolls^

A Most Violent Year

The Middle Mystery of Kristo Negro (Khavn)*

Ex Machina

Die Marquise von O… (Rohmer)

An Inn in Tokyo (Ozu)*

Big Hero 6

Images of the World and The Inscriptions of War (Farocki)

Corta (Felipe Guerrero)*

Le bel indifférent (Demy)*

Passing Fancy (Ozu)*

Inherent Vice

Mommy (Dolan)

Quality Street (George Stevens)

Les Nuits de la Pleine Lune (Rohmer)

Jupiter Ascending

Amour Fou (Hausner)

Selma

Shoah*

Fuck Cinema^

Bitter Lake (Adam Curtis)*

Broken Circle Breakdown^

We Are Many

Duke of Burgundy

Love is Strange

Chuquiago (Antonio Eguino)*

The American Friend*

Set Fire to the Stars

Catch Me Daddy

Blackhat

Hinterland

Two Rode Together

Patas Arriba

Relatos salvajes

Clouds of Sils Maria

Still Alice

The Experiencer (Michael Kohler)^

Cabiri (Michael Kohler)^

CHAPPiE

White Bird in a Blizzard*

Hockney”

Love and Bruises (Lou Ye)*

Coal Money (Wang Bing)*

Kommander Kulas (Khavn)*

The Tales of Hoffmann

Entreatos (João Moreira Salles)^

White God

Insiang (Lino Brocka)*

5000 Feet is Best (Omer Fast)*

Bona (Lino Brocka)*

Difret

Aimer, boire et chanter

May I Kill U?^

Bande de filles

Appropriate Behavior

The Golden Era (Ann Hui)+

Gemma Bovery+

A Hard Day’s Night+

The Divergent Series: Insurgent

De Mayerling à Sarajevo (Max Ophüls)

Marfa Girl

When We’re Young

Timbuktu (Sissako)

La Sapienza (Eugène Green)

Enthiran^

Serena (Susanne Bier)+

22 Jump Street+

Undertow (David Gordon Green)*

Delirious (DiCillo)*

Face of an Angel

Cobain: Montage of Heck

Wolfsburg (Petzold)

The Thoughts Once We Had

El Bruto (Buñuel)*

Marriage Italian-Style (de Sica)*

Force majeure

Workingman’s Death*

The Salvation (Levring)

Glassland

The Emperor’s New Clothes (Winterbottom)

The Avengers: Age of Ultron

Life May Be (Cousins/Akbari)

A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence

The Falling (Carol Morley)

Far From the Madding Crowd (Vinterberg)

Cutie and the Boxer^

Samba (Toledano and Nakache)

Mondomanila, Or How I Fixed My Hair After Rather A Long Journey*^

Phoenix (Petzold)

Cut out the Eyes (Xu Tong)

Producing Criticizing Xu Tong (Wu Haohao)

Colossal Youth (Pedro Costa)^

Accidental Love (David O Russell)*

The Tribe

Unveil the Truth II: State Apparatus

Mad Max: Fury Road 3D

Abcinema (Giuseppe Bertucelli)

Tale of Tales (Garrone)

Tomorrowland: A World Beyond

Coming Attractions (Tscherrkassky)*

Les dites cariatides (Varda)*

Une amie nouvelle (Ozon)

Ashes (Weerasethakul)*

Jeunesse dorée (Ghorab-Volta)^

La French

Inch’allah Dimanche (Benguigui)

San Andreas

Regarding Susan Sontag

Pelo Malo*

The Second Game (Porumboiu)^

Dear White People*

Spy (Paul Feig)

L’anabase de May et Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi et 27 années sans images*

Punishment Park*

Aquele Querido Mês de Agosto (Miguel Gomes)*

Black Coal, Thin Ice

Listen Up, Philip

Future, My Love*

Lions Love… and Lies (Varda)*

De l’autre côté (Akerman)

Les Combattants

London Road

West (Christian Schwochow)

Don Jon*

Mr Holmes

The Dark Horse*

Slow West

El coraje del pueblo (Sanjinés)^

Scénario du Film ‘Passion’ (Godard)*

Filming ‘Othello’ (Welles)*

Here Be Dragons (Cousins)*

Lake Los Angeles (Ott)*

Amy (Kapadia)

Magic Mike XXL

Hippocrate

It’s All True

I Clowns*

The New Hope

The Overnight

Sur un air de Charleston (Renoir)*

Le sang des bêtes (Franju)*

Chop Shop (Bahrani)*

Plastic Bag (Bahrani)*

Love & Mercy

Terminator Genisys 3D

Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief

The Salt of the Earth (Wenders/Salgado)

Mondo Trasho*

Le Meraviglie

True Story

Eden (Hansen-Love)

A Woman Under the Influence

River of No Return (Preminger)

Love (Noé)

Trois souvenirs de ma jeunesse

Ant-Man 3D

Today and Tomorrow (Huilong Yang)

Inside Out

Pixels

Fantastic Four

99 Homes

Iris (Albert Maysles)

52 Tuesdays*